The Language Comprehension Side of Things- Background Knowledge

Let me start by saying, I am not an expert on language comprehension. I’m not a Speech Language Pathologist (SLP). I’m a reading interventionist whose expertise is helping older students who are struggling in literacy. I love the foundational skills. I love helping kids crack the code. I love seeing that when kids really learn how to decode and encode multisyllabic words, the world suddenly opens up for them. Their confidence soars! But this year, I am finding I need to dig deeper into the other facet of reading comprehension… language comprehension.

This month I did a deep dive into the data of one intermediate intervention group. We’ve been working all year on the five components of literacy. I assessed phonological awareness, phonics, and fluency. We’ve been explicitly and systematically teaching foundational skills to fill gaps while keeping up with tier 1 content, vocabulary, and standards. However, I was disappointed with our midyear benchmark growth; I knew something was missing.

I went back to the Simple View of Reading

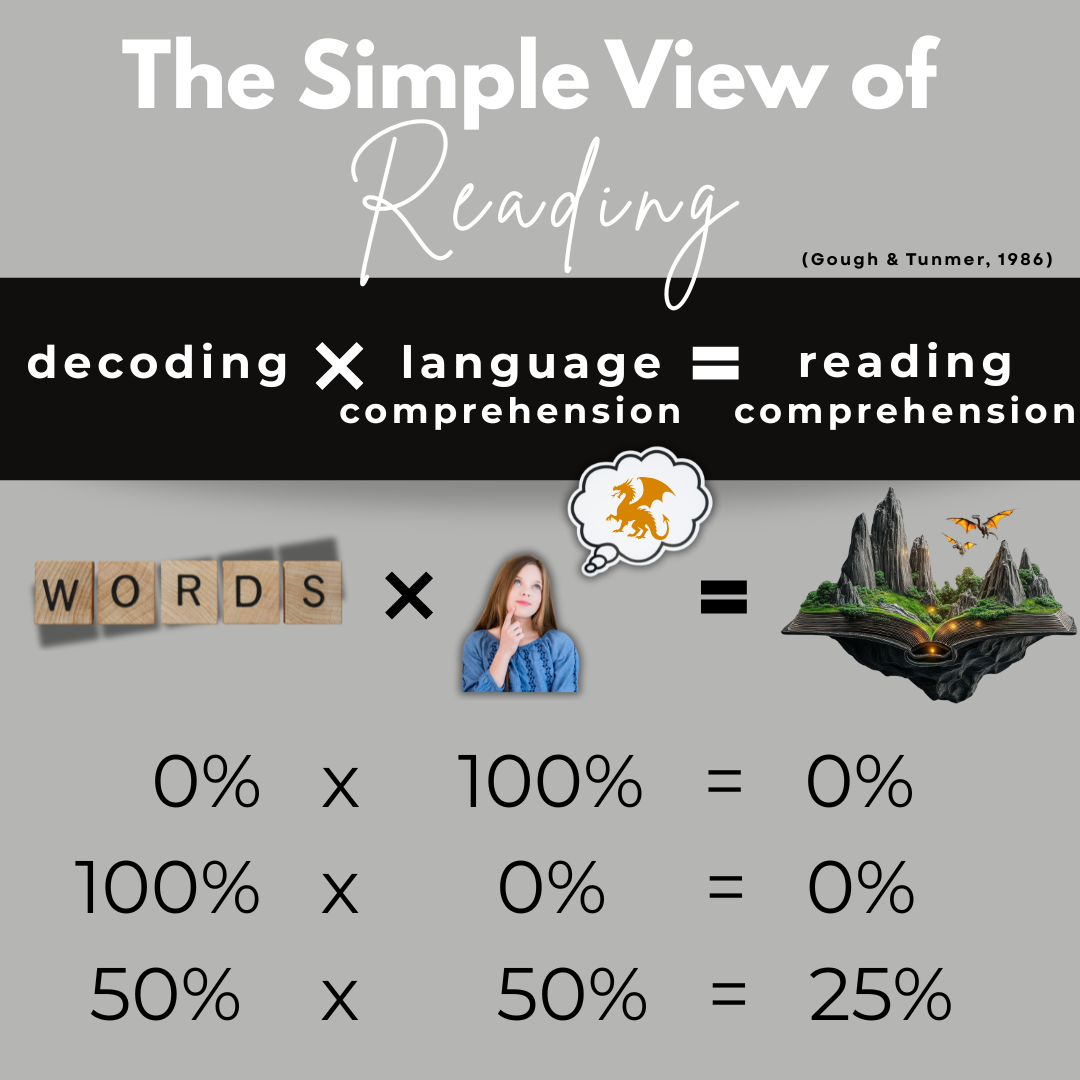

(Gough & Tunmer,1986).

This is a theory that states that reading comprehension is the product of decoding skills and language comprehension.

Decoding x Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension

Decoding is the ability to match letters to sounds to figure out a word accurately in a quick and fairly effortless way.

Language Comprehension is the ability to obtain meaning from spoken words and sentences.

These two components of reading are then put into a formula. Just like in a math equation, if either number is 0, the product is 0. So, if students are struggling to decode, their reading comprehension is negatively affected. When students struggle to understand spoken language, their reading comprehension will also suffer.

This intervention group has come so far in accuracy and fluency. Most are reading between 96%-99% accurately on grade-level passages! Our fluency is still a work in progress, but not a crisis. My main concern was that these students didn’t seem to be making gains in comprehension. Their lack of growth on benchmark testing as well as lack of independence and ability on class reading requirements had me baffled. I knew that language comprehension must be impeding their reading comprehension!

This is my unpolished, work-in-progress, starting-line dive into understanding (and remediating ?) language comprehension. I’ll keep you updated about our progress throughout the rest of the year, but this is how I began my language comprehension intervention.

First, I pulled two books off my shelf: Visualizing and Verbalizing for Language Comprehension and Thinking by Nanci Bell and The Reading Comprehension Blueprint, Helping Students Make Meaning from Text by Nancy Lewis Hennessy. These will be my guides, and I highly recommend them both.

The four pillars of language comprehension we will use for our objectives the rest of this year are: background knowledge, vocabulary, syntax and sentence structure, and visualizing. I’ll break each down in the coming weeks.

Let’s start with background knowledge.

Every year, there is one progress monitoring passage that drives the teachers crazy. It’s about a girl who visits a nature preserve with her teenage brother. Our students usually bomb it, and we feel momentarily defeated. The problem is that many students struggle to decode the words nature and preserve, and if they do decode them, they don’t have much background knowledge about nature preserves. This year I did an informal, quasi-experiment. I had a group of 6 students read the passage as normal. I waited two weeks.

I then taught an eight minute mini-lesson that included decoding the words nature and preserve using phonics and morphology, and also facts about what nature preserves are. After the lesson, each student reread the passage. I was confident enough time had passed that it wasn’t practiced and that the amount of instruction in two weeks would not account for above-average growth. The results shocked me. All of my students’ accuracy, fluency, and comprehension increased substantially! I just validated Hennessy’s claim that, “Effective instruction includes strategies and activities that activate or assess, build, and connect background knowledge to a related text.” (Hennessy 2021).

Actual experiments about background knowledge are not new. The Baseball Study (Recht & Leslie, 1988) has been referenced in many publications including The Knowledge Gap. The gist of that study is researchers had middle school students read an article about a baseball game. The students were either poor or proficient readers and had either little or extensive baseball knowledge. So, four groups were created: 1) students who were high readers and had extensive baseball knowledge, 2) students who had low reading proficiency but had extensive baseball knowledge, 3) students who had high reading proficiency, but little baseball knowledge, and 4) students who had low reading proficiency and little baseball knowledge.

The results were that the students’ knowledge about baseball ended up being more impactful on their reading comprehension than their actual reading ability!

I plan to tune in to this correlation more in my class. Who has background knowledge? How can I foster students’ prior knowledge so they can be more successful in their independent reading comprehension? How can I build background knowledge for students who lack experience or language-rich environments? How can I aid students who have language deficits to increase this part of the equation for them?

I am not claiming to be a researcher or make any scientific claims about causality. However, I do believe that teaching real content and knowledge is important. Knowledge is like Velcro; it’s sticky.

I have seen first hand that the more background knowledge students have, the more accurately and fluently they read and the more connections and inferences they can make.

Teacher Action Plan to Increase & Activate Background Knowledge:

Teach real content. Advocate for a knowledge-rich curriculums rather than random disconnected texts.

Create short mini-lessons to build background knowledge and teach content-specific vocabulary prior to giving independent reading, especially for struggling readers. Show pictures, videos, maps, and tangible show-and-tells to build prior knowledge.

Whenever possible, use knowledge-building content to practice other reading components. Integrate phonics, morphology, fluency, and vocabulary into content lessons.

Use skills to aid comprehending content-rich texts rather than using texts to teach or practice a skill.

You can revisit the four parts in the Language Comprehension Side of Things Series here:

1- Building Background Knowledge

2- Vocabulary

3- Syntax and Sentence Structure

How else do you build student knowledge? I’d love to hear your comments below!

Next week, we will take a look at building student vocabulary!

~Bri